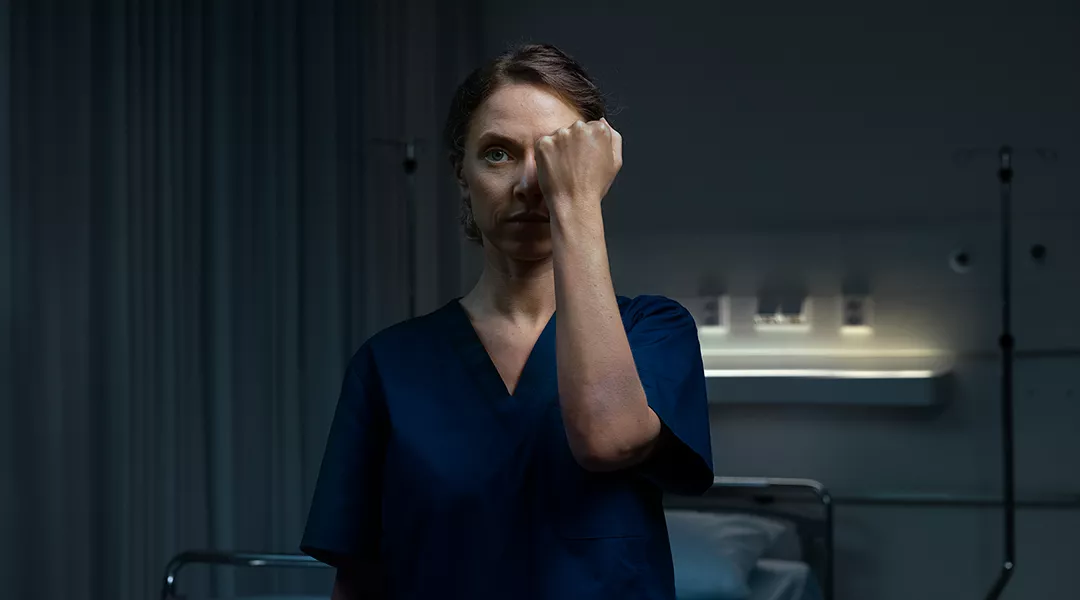

The Finnish name of the campaign, Nyrkkisääntö (lit. ‘rule of fist’), is the Finnish equivalent of the English phrase ‘rule of thumb’, meaning a simplified and general guideline for every situation. Every person in Finland knows what it means without having to be told, although the origin of the word is unclear to many – how and why we started to use this word for this meaning.

Nyrkkisääntö was chosen as the name of Tehy’s campaign because it perfectly describes our goals: addressing violence must be the rule of thumb at every workplace.

The somewhat obscure origin of the word also well reflects the attitudes towards workplace violence in the social, health care and education sector. The concept of a non-violent workplace is widely accepted in society, but when we go to the roots of the phenomenon, to everyday working life, it is as though there is a tacit acceptance of violence – it becomes ‘normal’.

We must move away from acts of violence hidden from the eyes of the general public and the normalisation of insecurity to ensuring that a non-violent and safe workplace is a matter of course and the right of everyone working in the social and health care sector.

A shortage of nurses increases the risk of violence

Acts of violence in the social and health care sector are increasing, while the need for care keeps growing as the baby boom generation ages. In the future, the larger amount of care work will mean a larger amount of workplace violence if the current trend continues. However, violence can be reduced considerably.

Working alone is one of the most significant factors that increases the risk of violence. A shortage of nurses leads to employees being alone in many situations that are known in advance to pose a high risk of violence. Decision-makers must ensure the funding and staffing requirements of the social and health care sector in order to prevent these obvious high-risk situations.

Another immediate measure called for by Tehy is the initiation of a broad national enquiry into this matter. The enquiry should lead to minimum standards being established for the social and health care sector for the prevention of factors of violence and for follow-up work.

Occupational safety and the methods to maintain it are standard in industry, but, unfortunately, this is not the case for the social and health care sector. Relatively similar threatening and dangerous situations keep occurring throughout the country, but individual workplaces do not wake up to the situation until the worst happens.

Occupational safety would improve significantly if national standards were established for the prevention of violence. It would also improve the efficiency of individual workplaces if they did not have to come up with solutions for threats of violence from scratch. This would simultaneously increase employers’ certainty of better compliance with the Occupational Safety and Health Act. This project could be led by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, for example.

We wish to cooperate with both lawmakers and employers. After all, it would be in everyone’s best interests if no workplace violence occurred in the social and health care sector.

The only punishment for assaulting a nurse is fines

The Criminal Code of Finland lays down harsher punishments for violent resistance to a public official than for basic assault. From the lawmaker’s point of view, a police officer and a doctor in a public-service employment relationship are more valuable than e.g. a paramedic or a registered nurse if they were to be subjected to violence in the same situation. This difference in appreciation is difficult to understand or justify. Why should an assault against a doctor lead to a prison sentence but an assault against a nurse only to fines?

Tehy calls for ‘violent resistance to a public official’, as specified in the Criminal Code, to be extended to cover all social and health care personnel in the future. This could discourage people from assaulting nursing staff once awareness increases of the punishment laid down for the act being more severe than usual.

Another legislative amendment sought by Tehy concerns the damages that the offender is sentenced to pay for the offence. The victim of a violent crime may seek damages for the pain and aches they have suffered through legal proceedings.

For an assault that leaves no permanent marks and causes no broken bones, the damages payable are usually only a few hundred euros. This compensation is often disproportionately small, considering the shock caused by the incident to the employee and that it may even have a permanent impact on the employee’s work ability.

Moreover, those who subject social and health care professionals to violent crimes are often practically insolvent. In such cases, the State Treasury can pay the damages owed to the victim instead of the offender, but this leads to an automatic basic deduction of EUR 220 from the damages payable. The difference that is left is often no more than a few dozen or a hundred euros. It is difficult to understand why a ‘co-payment’ has to be deducted for an act of violence encountered in work carried out for the common good.

With the level of damages being so low in the first place, the small amount of compensation is usually the last straw for an employee who has experienced a lack of fairness and appreciation. Tehy calls for the removal of the basic deduction specified in the Act on Compensation for Crime Damage in cases in which the victim is targeted by a crime due to their work responsibilities.

Read more about these and the other goals of Tehy at https://www.tehy.fi/en/current-tehy/black-eyed-day

P.S. For the reader who wondered about the origin of the word ‘nyrkkisääntö’: the width of a man’s fist is roughly ten centimetres. The same fist that many nurses have taken to the jaw.

Read more about violence in the social, health care and education sector on the Black-Eyed Day campaign website. You can also participate in the campaign on social media. Also listen to the audiobook ‘Nyrkkisääntö’ on Spotify to hear nurses talk about the violence they have experienced in nursing work. The book is edited by award-winning non-fiction author Jenny Rostain.